We know that the recording of history is only as inclusive as the authors and those invited to participate, and that past milestone anniversaries were not “of, by, and for the people.” We are working to correct that in Philadelphia in 2026. You can read more about the past commemorations, why they mattered, and what we can learn from them.

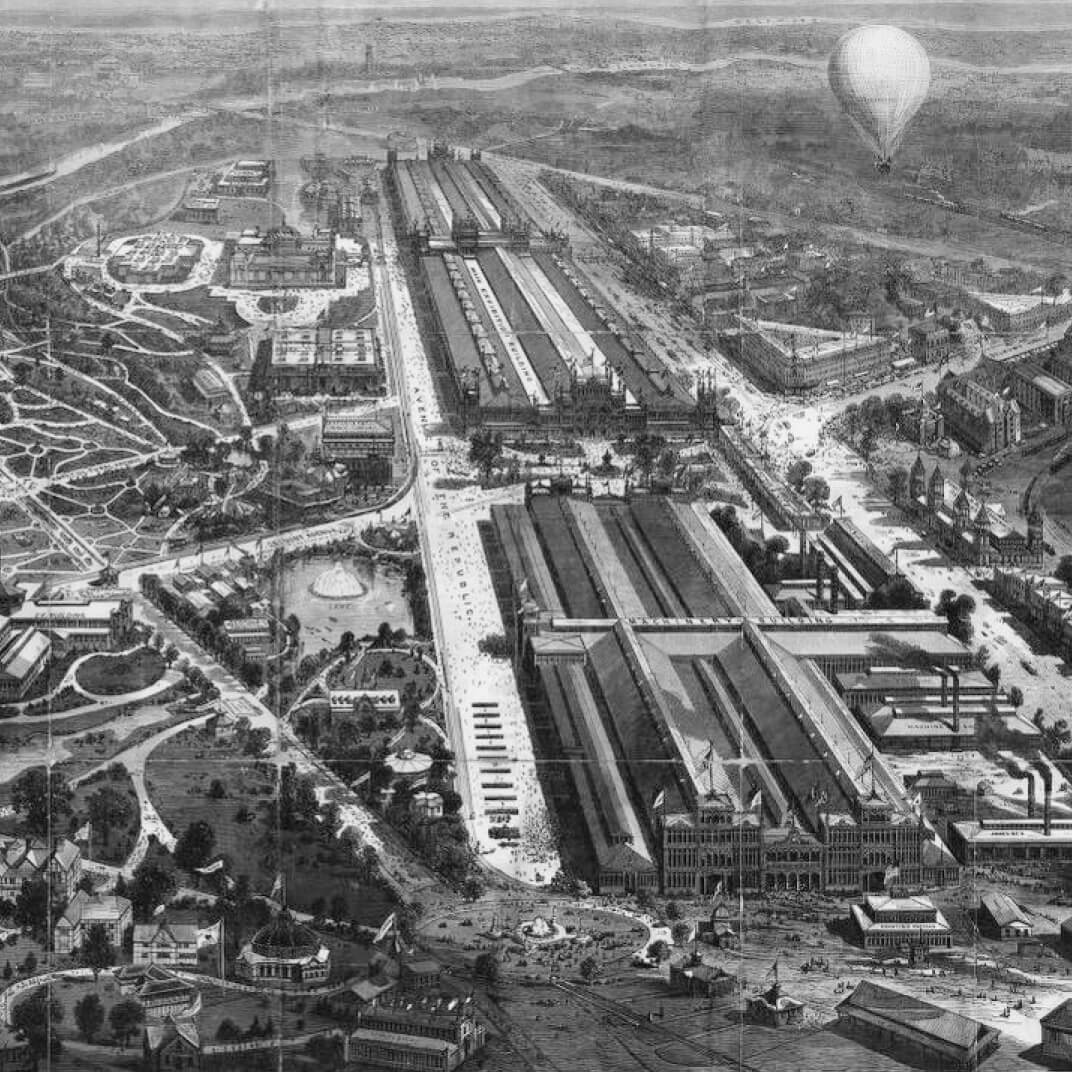

In 1876, the world gathered in Philadelphia to mark the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence – and the first World’s Fair held in the United States. More than 10 million visited the “Great Exhibition” that year – located in what is now called the Centennial District on more than 200 acres in Fairmount Park – which promoted American resources, innovation, and arts and culture as well as international pavilions. The Centennial Exhibition declared the United States and Philadelphia, the largest city in the US at the time, as the “workshop of the world.” The Smithsonian’s modern collection and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, among other legacies, date back to this commemoration.

In 1926, Philadelphia yet again hosted a World’s Fair to commemorate America’s 150th birthday. John Wanamaker began bringing together fellow Philadelphians around this goal in 1916. The Fair ran from May to November of 1926 and stretched from the Naval Yard to Packer Avenue in South Philadelphia, from 10th Street to 23rd Street. Highlights included pavilions from thirty one states and nine countries, a recreation of colonial Philadelphia’s High Street (now Market Street), and an eighty foot high, lit replica of the Liberty Bell. FDR Park, Marconi Plaza, and the Sports Complex remain as legacies from the 1926 celebration. However, the commemoration was troubled due to a lack of funding and an inability to attract as many visitors as the Centennial in 1876.

Famous Philadelphia urban planner Edmund Bacon began dreaming in the 1960s about how the city could mark the nation’s bicentennial in 1976. A contentious planning process ensued that included protests to ensure minority voices were included. Ultimately the City formed the Bicentennial Corporation to raise funds and generate widespread public support, and President Johnson created a national entity to oversee funding and content from the federal government. Though the federal government did not approve the plan presented by the city, and racial tension around themes and location continued, the 1976 commemoration did feature a full year of programming: daily activities leading up to July 4th, the ceremonial moving of the Liberty Bell from Independence Hall to a custom-built pavillion, and a time capsule buried in the Old City section of Philadelphia. Built legacies from 1976 include the African American Museum, the Independence Seaport Museum, and the addition of the three blocks encompassing Independence Hall to the Independence National Historical Park.